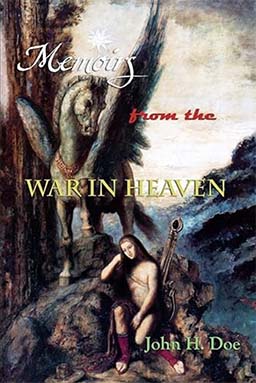

My recollection of the pivotal moment in my visions: it was tense. That is what I seem to recall of when I entered the field where Satan was to be cast out. I had been fighting alongside angels in the War in preparation for what was about to commence, inspired by Joan of Arc the whole time this had been happening. I had seen the punch-through in the map of HALOSPACE where there was victory, final victory: confidence was high. But this was no mean task. Michael, Mika-el guided me as I faced SATAN, and I almost tried to stare him down with the Archangel powering my eyes: my (almost) error. Repositioning, I looked up, directing SATAN’s gaze to Mika-el’s, above and below, in a column. Then I shot, the psychic trigger that cut the last cord that tied him to HEAVEN, and SATAN roared: NOOOOOOOOOOOOOOO! As the Archangel forced him down, down, out of HEAVEN cast.

Contrary to popular opinion, the statement “I think therefore I am” can, in fact, be refuted. You can deny your own existence. It doesn’t even have to be illogical to do so, either. We have something that “looks out”, and that is what most people consider their own personal “I am”. This is what Descartes is talking about in his famous statement: we are, that cannot be denied. If we denied it, then what is doing the denying? Whatever that is, that must be the “I am”. Without it, we could not do anything at all, because we would not be anything at all to do it. But could it not be just an illusion? What if that which looked out were actually an extension of a greater thing that looked out, which you were not aware of, that lends you the sensation of authentic consciousness? That other knows what it is to look out for real, you just think you do. That would mean your “I am” is not, not really. It’s just borrowed, it is only a leaf on a tree, and is not the being that is actual, that is the tree, like it thinks. And that’s within logic. If one were not to take logic for granted, we could go to town on Descartes’ irrefutable. Then nothing is sure, and you know what? We do take logic for granted. Nothing really to say that logic has to be how things work, just a history that it does. Something you might want to think about.

There is no such thing as “have to”. Nothing “has to” be as it has been, as it seems, sometimes, how it must be. Just because it doesn’t make sense if, for instance, logic didn’t have to be logical, doesn’t mean logic has to be logical. Why does it have to make sense? That’s inductive thinking, as is all logic or metalogic, when it comes down to it. Because it’s seemed to work a certain way from as far back as it has been recorded, doesn’t mean it “had to” be that way, nor that it “has to” be that way. It is another astounding coincidence that things make sense. That we can rationally conceive of theories that model how certain things have worked, and continue to work. Einstein said so himself, “The most incomprehensible thing about the world is that it is comprehensible.” I think he may have understood what I’m talking about.

Don’t ever think at any time that you believe(d) nothing. That is impossible. We are walking around in the everyday world with a thousand assumptions at any given time. Some are useful, some are not, some are true, some are false. They don’t have to be true to be useful, but generally, you’re better off believing things that are true. Science is a way to organize beliefs in such a way that one tries to weigh them according to evidence. Science also believes things, some things useful, some not, etc., etc. There is an art to science, and many who believe in science miss this. But one piece of advise: believe in something that is science over something that is not. This is prudence. And if you want a challenge, try to believe nothing, and end up with something. This is the most basic desire of science.

Descartes said that it is useful at some point in the history of our minds to doubt all things. He actually didn’t go far enough, in that “I think therefore I am” lends a certainty to basic logic. Logically, if I were not, then I could not be thinking. Substantively, as far as we are used to very fundamental things behaving, it is irrefutable. But if we do not hold that this is sure, that things could possibly behave in ways they never have, not in any case we have studied, we come upon a very interesting viewpoint. It is to say that we do not notice that miracles happen every day, simply because they happen every day. If we do not take for granted things holding together: solidity, cause and effect, motion itself: we may begin to see how awesome is the most common of things. How magnificent the verymost mundane. We may begin here to make sense of things. And wonder.

We are born wired in the ways of space and distance, and the ordering and passage of time. We are born knowing an astounding number of things. How is it we first grasp at anything with our hand? That we imitate a sound we hear? To think of one thing as tasting different from another, to look and to comprehend size, more than one vs. the one; spectacular is such faculty. Now this is astounding, too: we are born knowing how to learn. How much effort has been put out to make our machines do so? Pleasure and pain we are born knowing, play and boredom. And yet this is nothing close to what we need as tools to live in this world. What does that speak of?

The question is not, “what do we know?”, but “what can we forget?” Can we truly forget the notions of time and space? Can we forget being? For if we truly wish to do as Descartes advised, we must forget these things. Let us to forget functioning of any sort: can we do that? Perhaps that is the key. This is to doubt the logic of the very of mundane, that logic which allows one to be certain that when one says, “I am”, he cannot be refuted. Let us then be able to refute that, to think in a situation where nothing makes sense, and maybe we can go deeper down the rabbit hole than Descartes himself thought it went. And so perhaps we may approach that lesson that Jesus Christ once told me: “Work is magic.”

Doubt is not a sin. It may be that by faith we are saved, but it is by doubt that we learn. Even if that lesson is merely that we should have had faith in the first place. For it is better to question everything than to question nothing. Some of us are born with a certain certainty that allows the individual to understand things; the rest of us go by trial and error, and it is doubt that is more a friend than faith. Let us rather doubt that there is a God at all than believe in a God we do not understand, a God who is not love. There is virtue in that exact righteousness, and believe that that is righteous. You believe in nothing if you believe in a God who is not love.

How in the interlocking of gears, one turns another: that is magic. How gravity pulls a thing that is dropped, without fail: that is magic. I spot the teacup on the table: just that is twice magic, if not more. There are things that are magic within magic within magic. Whenever you google something, those are magics in force, eldritch incantations being spoken by machine, machines which are levels upon levels of magic themselves in operation. And we do not notice the miracle of the simplest forms of working. How does anything at all work, at all? That is the magic. The cause and the effect, the most trivial of physics: we should not assume that these are guaranteed, for free. And if we see that, the wonder of the barest of function, we gain one glimmer of what it must be, what Einstein wanted: to know the mind of God.